replotting three dimensional data

One of my favorite things to do when I read a paper is to replot the author’s data in a way I like better.

Sometimes my reasons are scientific. The bar plot reigns supreme over most academic papers I read, yet bar plots are usually used to hide information from the reader: by distilling a distribution of data into a single number, lots of information is lost. Other times, I just want to see whether I can remake the author’s plots, and if so, how fast I can do it.

But sometimes I come across a figure that I instinctively don’t like and want to come up with a better way of plotting it. Which is what happened in an airport waiting for an outboard flight out east over winter break.

I started reading this paper mostly because one of the authors is in my department and I wanted to see whether they could really use the term behavioural hypervolumes seriously. (They can. Why they don’t say ‘variation in behaviors’ instead is beyond me.) The authors measured the boldness (how long they took to start moving again after being scared), foraging aggressiveness, and overall activity levels of individuals from five spider species.

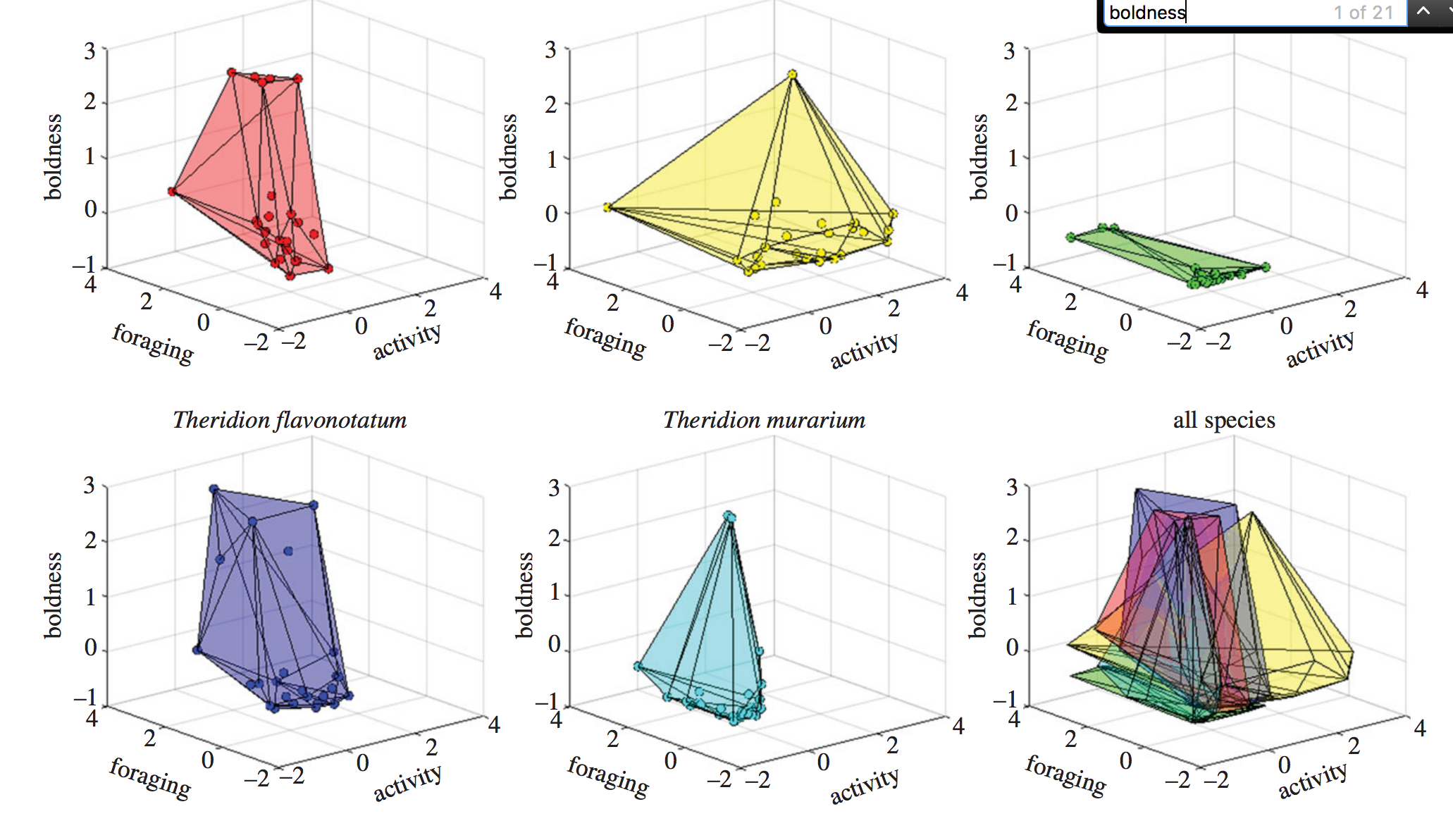

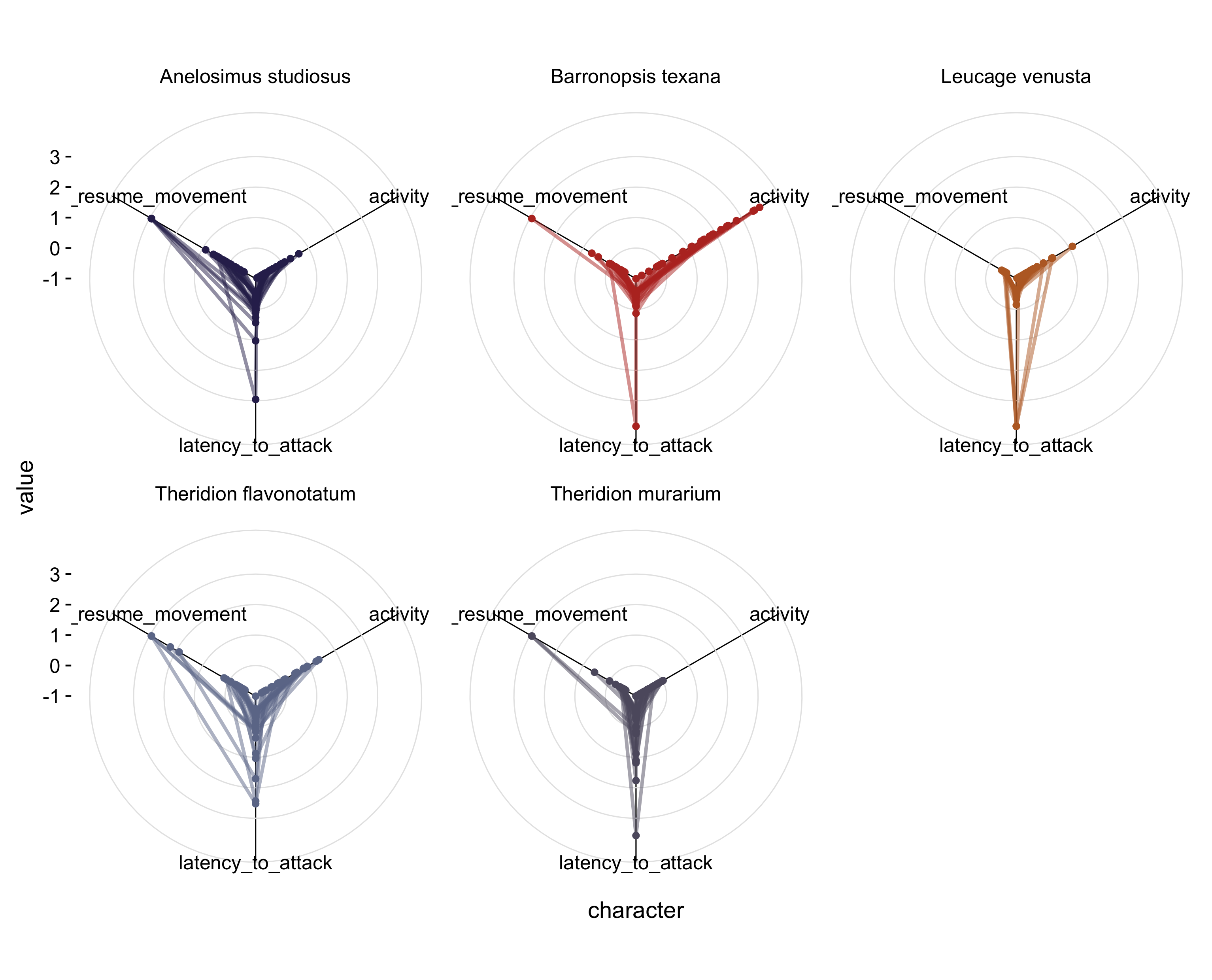

The authors’ challenge was coming up with a way to present three-dimensional data (the three variables they measured) on a two dimensional page. Here’s the result:

This is the sort of figure I cringe at. In their attempt to show all the data at once, the authors are sacrificing the ability of someone to actually take something meaningful away from the figure. Specifically, it’s difficult for the reader to understand the foraging, activity, and boldness for each of the data points.

Admittedly, you don’t need to know the position in three-dimensional space of each data point to get the point the authors are trying to convey in the paper: the species apparently differ in the ‘volume’ of space occupied if you where to form a shape by connecting the most peripheral data points. Species that have lots of variation in their behaviors will have big ‘hypervolumes’; species where there is little between-individual variation will have small ‘hypervolumes’. Still, it’s really difficult for the reader to judge, for example, the difference in the hypervolume size between the two species in the first column.

Can we plot it better? That’s what I was wondering as a grappled with the Bingo hotspot to download the data from Dryad.

reading in the data

Let’s first go ahead and read in the data. The data were provided as an Excel file; I saved it as a csv, cleaned up some of the column names, and renamed the file.

# load packages

library(tidyverse)

library(magrittr)

# read in data, factoring species

df <- read_csv("~/Downloads/pruitt.csv")

df$species %<>% factor

# scale each variable to enable better visualization

df$activity %<>% scale

df$latency_to_attack %<>% scale

df$latency_to_resume_movement %<>% scale

Note that the %<>% is from the wonderful magrittr package is used to pipe the object on the left-hand side to the function on the right-hand side, and save the result of the function to the original object. x %<>% factor is shorthand for x <- x %>% factor or x <- factor(x)

replot

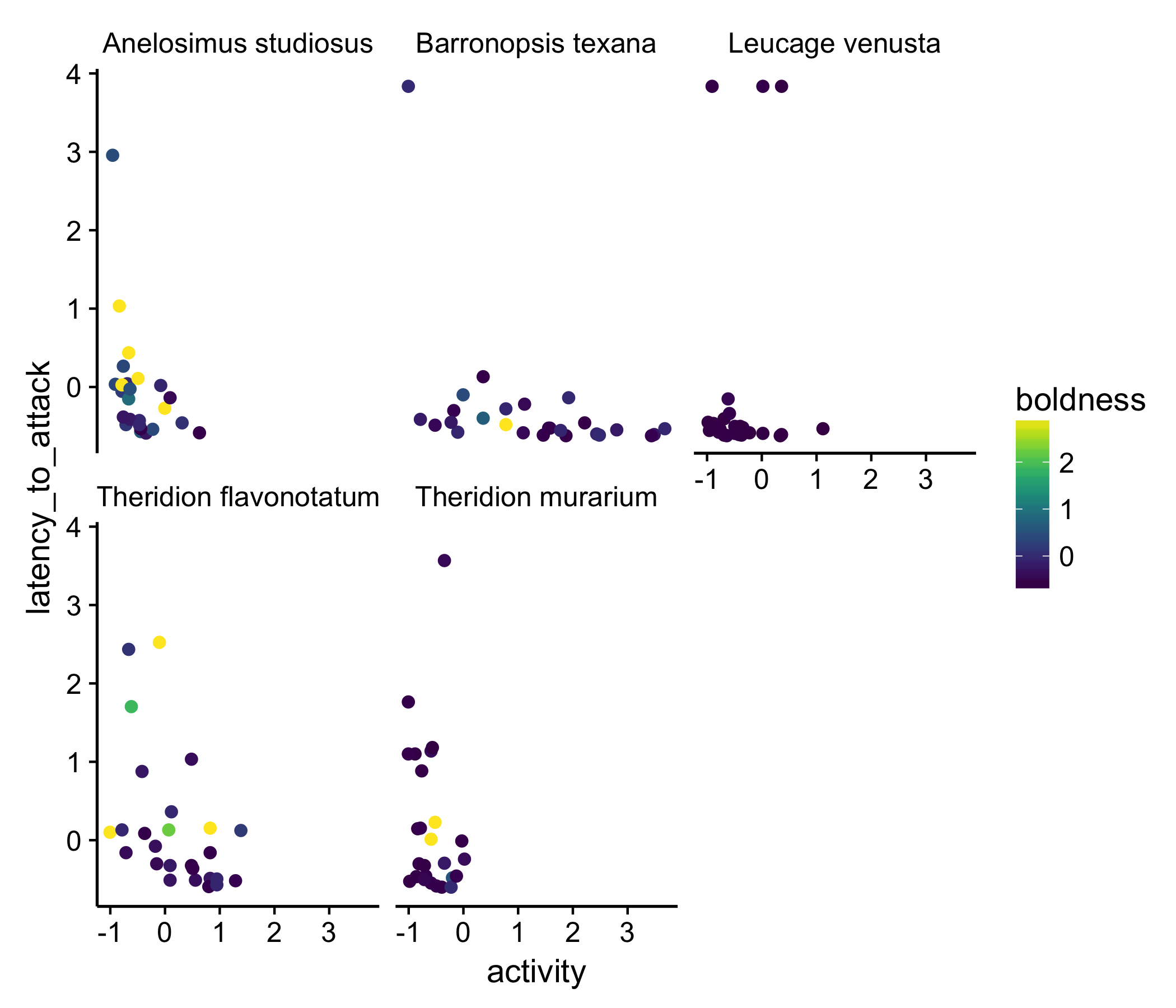

An obvious first stab is to represent two of the variables by the x- and y-axes and a third by the color of the data points.

ggplot(df, aes(activity, latency_to_attack)) +

geom_point(aes(color = latency_to_resume_movement)) +

facet_wrap(~species) +

scale_color_greens(name = "boldness") +

theme_mod() +

add_axes()

(I’m using a ggplot theme I like here, theme_mod, and some helper functions, like add_axes(), that are defined here.)

This isn’t the best plot but it shows the data, in, I think, a better way than the three-dimensional plot. Part of what we notice with this presentation is that most of the data points are purple: in other words, most of the spider measured are not very bold. At least to me, this wasn’t clear in the original plot of the data.

a different approach

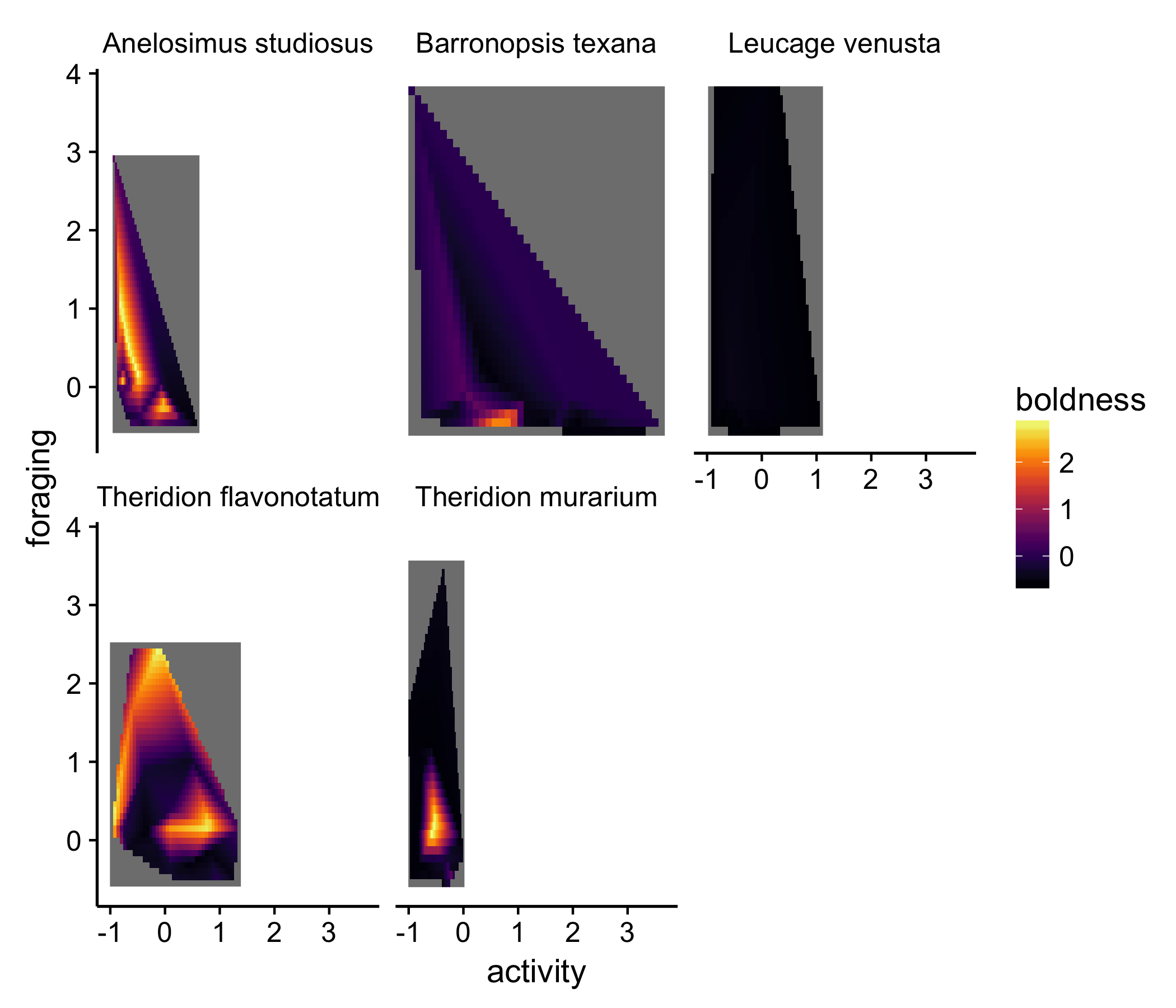

Is there a better way we can plot these data? This sort of dataset is not uncommon for biologists to want to visualize. One approach people have taken in the past, to better show the relationship between all three variables, is to use a surface plot. Though using a surface plot means we no longer are looking at the data and move to showing some abstraction of summary of the data, they can often be useful.

Below I should how we can use the feilds and akima packages to create a function that returns a surface for each species. This amounts to estimating each species boldness for each combination of activity and latency of attack. I then apply that function to each species in the dataset and plot the result. This turns out to be a lot more readable, shorter, and more efficient than the approach I would have taken a year ago: create five subsets of data (one for each species), generate the surface for each, save each surface as a separate plot, then combine at the end.

First, we define a function that creates the surface for us:

require(fields)

require(akima)

get.inter <- function(df){

y <- with(df, interp(x = activity,

y = latency_to_attack,

z = latency_to_resume_movement))

interp2xyz(y, data.frame=TRUE)

}

Then we using piping to (1) get the surface for each species and (2) plot the results all in one big step

new_plot <- df %>%

group_by(species) %>% # group by species

nest %>% # this creates a column, data, with all the data from each of the five species

mutate(

inter = purrr::map(data, get.inter) # apply the get.inter() from above to each of the species

) %>%

unnest(inter) %>% # unnest to get back a full data frame with all the results

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y)) + # set up out plot

geom_raster(aes(fill = z)) + # provide a geom to use

scale_fill_viridis(option = "B", name = "boldness") + # use a perceptually uniform color scheme

facet_wrap(~species) + # make a separate plot for each species

theme_mod() + # add a theme

scale_color_continuous(na.value = "white") + # make NA values white

labs(x = "activity", y = "foraging") + # add labels

add_axes() # add axes

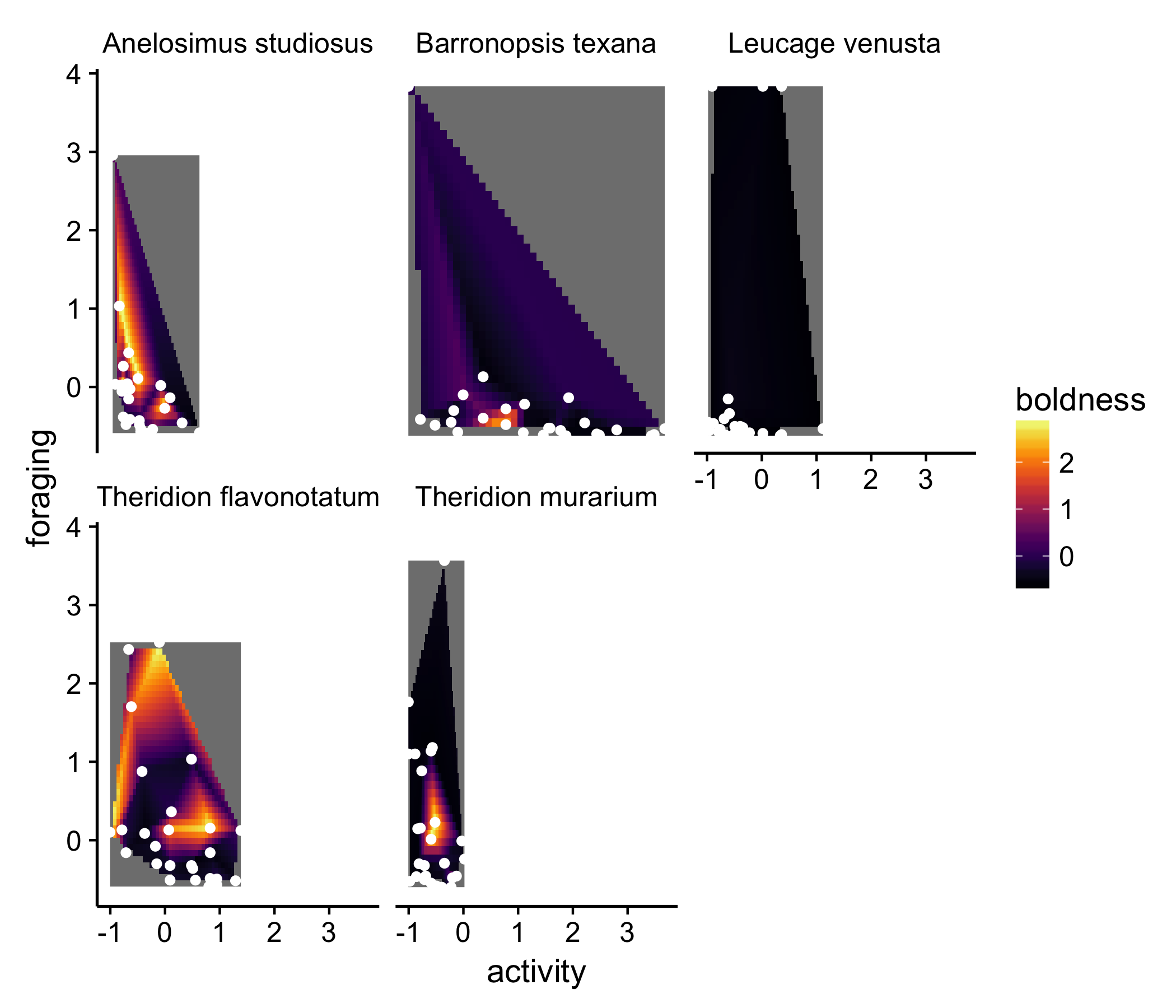

In this presentation, other aspects of the dataset are emphasized. For example, for both the species in the left-most column, there are very bold individuals, but the bold individuals appeared to have different activity and foraging tendencies in the two species. It’s important to note, though, that a lot of these trends are driven by a couple individuals, which the original replot shows. While abstractions like the surface plot are useful, they often hide information. I think it’s actually easier with this type of plot to estimate the difference in ‘hyper volumes’ among the species.

We could improve on this point by actually layering the actual data on top of each of the surface plots. Luckily, ggplot makes this easy:

newplot + geom_point(data = df, aes(x = activity, y = latency_to_attack), color = "white")

but still…

None of these solutions are really satisfying. The goal of the figure is to show that the ‘behavioral hypervolume’ differs between species. None of the above solutions really do that.

The radar plot is, I think, an under-utilized plot type to show multidimensional data, especially when the point of the figure is show how different groups differ in multiple dimensions. There are some whacky ways people have attempted to solve this in the past, but I think radar plots offer a good solution without being too foreign or un-scientific. It’s also a pretty general solution. With a 3D plot like the authors’ chose, you can’t add an additional variable; radar plots can incorporate plenty more variables, and are thus useful for showing all kinds of multidimensional data.

The radar plot is similar to to a parallel coordinate plot, in which each variable gets its own vertical axis, and observations and united by lines. The reader can go left to right, following a given line (observation), comparing the observation with the other points. I often find parallel coordinate plots to be overwhelming, however. Radar plot make things look a little neater by wrapping the parallel coordinate plot around so that it forms a circle instead of a straight line. This adds an extra dimension to the visualization, gives it greater depth, and creates a shape that can be easily compared between categories of observations.

Enough talk: let’s see what these data look like plot in a radar plot. Again, I’m using some helper functions I’ve declaring in a script elsewhere:

df %>%

mutate(id = 1:nrow(df)) %>% # create a variable that keeps track of observations

gather(activity:latency_to_resume_movement, key = "character", value = "value") %>% # wide -> long format

arrange(character) %>% # this is key!

ggplot(aes(x=character, y=value, group = id, color = factor(species))) + # set up the plot

geom_line(aes(color = species), size = 1, alpha =0.5) + # draw lines

geom_point() + # draw points

scale_color_alpine(guide = F)+ # set the color scheme. This one is based on a beer bottled I liked

theme_mod() + # change the default theme to something cleaner

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_line(), panel.grid.major.y = element_line(color = "grey90")) + # add gridlines back in

coord_radar() + # add coordinate for radar plot

facet_wrap(~species) # create a separate plot for each species to make things less chaotic

That’s a bit better. Now for each species, we get a sense of the variation in each of the behaviors and can easily compare between species.

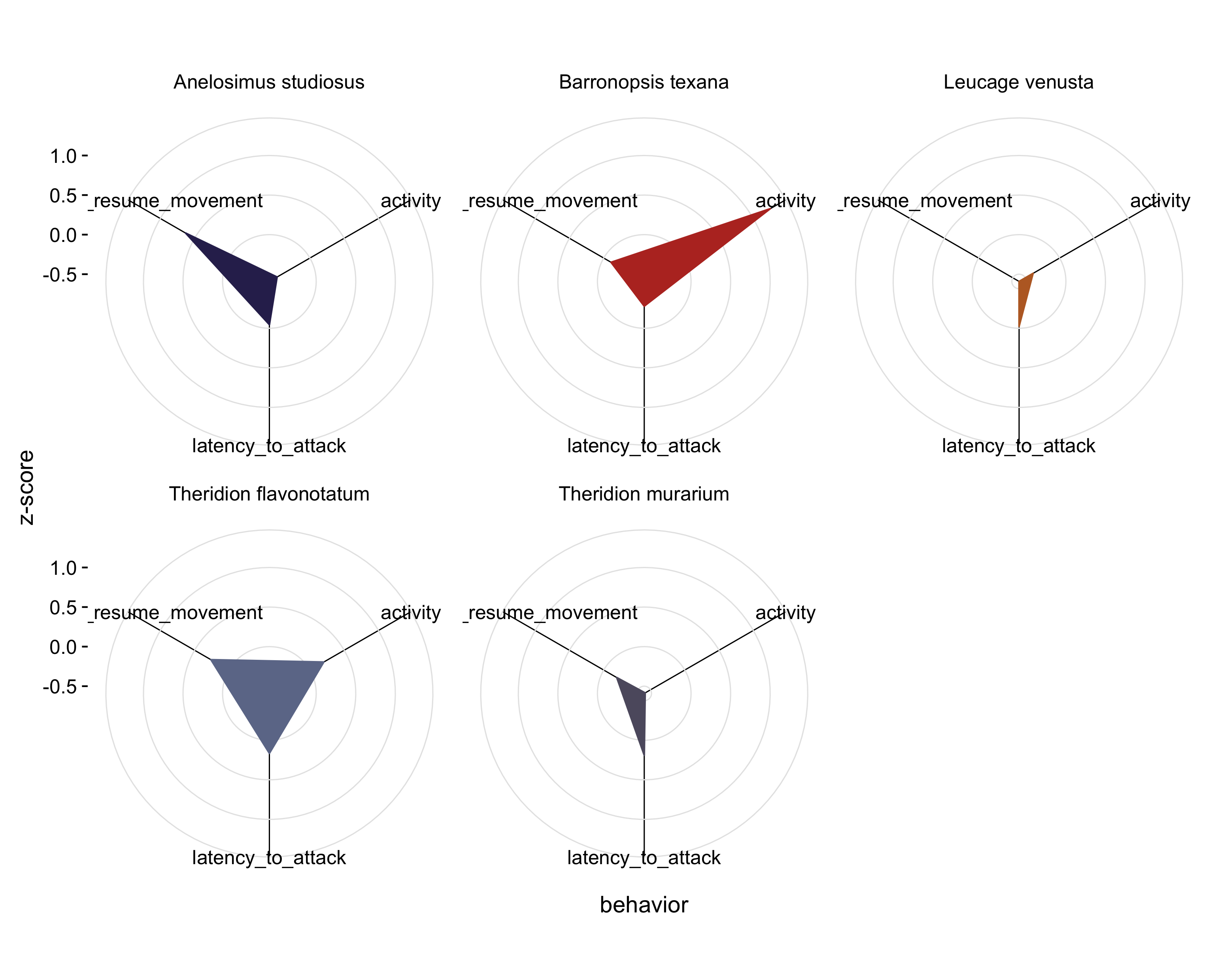

But the point of the original figure was really to show that show species have greater ‘hypervolumes’ than other species. Perhaps a simpler way of showing that is to create an average behavioral profile for each species and plot that instead:

df %>%

group_by(species) %>% # group by species

summarise_each(funs(mean)) %>% # create a mean for each species

mutate(id = 1:nrow(.)) %>% # create an id for each species

gather(activity:latency_to_resume_movement, key = "character", value = "value") %>% # wide -> long

arrange(character) %>% # this is key!

ggplot(aes(x=character, y=value, group = id, color = factor(species))) + # set up the plot

geom_polygon(aes(fill = species), size = 0.5) + # add the shape

scale_fill_alpine(guide = F)+ # set the fill

scale_color_alpine(guide = F) + # set the color

theme_mod() + # change the theme to something cleaner

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_line(), panel.grid.major.y = element_line(color = "grey90")) + # change the gridlines

coord_radar() + # add a coordinate system for radar plots

facet_wrap(~species) + # made a separate plot for each species

labs(x = "behavior", y = "z-score") # make the axis labels clearer

Now, I think the point the authors’ were trying to make comes through a bit better. It’s clear that some species (i.e. Theridion flavonotatum) have a high latency to attack, latency to resume movement, and are fairly active, while other species (i.e. Leucage venusta) show a low latency to attack, low latency to resume movement, and low activity levels. We can see, in two-dimensional space, that the ‘behavioral hypervolumes’ of the species differ. This plot could even be improved by inverted the latency metrics so that larger values correspond with more extreme or bolder spiders, instead of larger values (= large latencies) being relatively shy spiders.

take-aways

- 3D plots often seen like a neat idea; they are rarely practical

- try plotting your data several ways before deciding on a presentation

- focus on what the story you want to tell or the main point of a figure is

- radar plot are a useful technique to plot multivariate data